I have often heard the approaching footsteps of a romantic breakup by passively listening to other people’s dead-end dialogues. Reading Roland Dubillard’s Diablogues in middle school precociously instilled in me a thudding fear of misunderstandings leading to absurd exchanges, annihilating the possibility of any kind of decent conversation. This fear is, to this day, still well-established in my mind, and sometimes forces me to settle for silence. Then one day, music came into my life. I grew up during the era of Glee and mashups — already as a teenager, I was lamenting not being able to listen to two songs at once, one in the left earbud and the other on the right side, disavowing technical innovation and the legacy of stereo sound. Echoing, perhaps, my tortured romantic reveries, I dreamed of listening to two voices — and two stories — at the same tempo.

The book has not been officially translated, but the title means something like ‘the devil’s dialogues’. The Devilogues maybe?

In 1964, while conducting his research as a student in psychobiology, American neuroscientist Michael Gazzaniga discovered the split-brain phenomenon in humans, thus taking part in theorizing the current understanding of the lateralization of brain function. In an approach geared towards popularizing science, it is generally agreed that the left hemisphere of the brain controls all numeration, language, writing and reasoning functions ; while music, intuition, spatial orientation and artistic skills are regulated by its right hemisphere. Or — to put it even more simply — “artistic” individuals seem to primarily use their right cerebral hemisphere to bring their projects to fruition, with the left side serving the same purpose for “scientific” personalities. Could we believe in the possibility of a musical translation of this phenomenon? This research matter, embodied in my work both formal (as a music producer) and informal (as the curator of niche private Spotify playlists), rises to the top of my pyramid of obsessions.

When talking about duets, love songs rule the game, most predominantly on tracks within which two lovers answer each other and take turns confessing their feelings in perfect harmony of melodies and allocated speech time. But what about those dialogues of the deaf that I relentlessly obsess over in an attempt to find comfort in the universality of my emotional disillusions?

I stumble upon them again in the form of duets in which the singers share a melody in order to simultaneously enunciate different lyrics, providing the listener with two opposite but complementary points of view of the same narrative. It seems we can take the liberty of understanding both parts of a musical duet as catering to one brain hemisphere each, like a thesis with its built-in antithesis calling for both reason and intuition and enabling the listener to choose which one to believe in. Should I listen to the devil or the angel on my shoulder? Should I sing along to Frank’s (hopeful) or Nancy’s (resilient) tune when Somethin’ Stupid starts playing at karaoke night? How to decide which ear to trust?

You are the outline of a memory

Your smile fades in the summer

(So lost and disillusioned)

Place your hand in mine

(Are we alone? Do you feel it?)

blink-182 - Feeling This

Navigating the Genius website lyrics database, I find myself fascinated with these lyrics hiding in between brackets. I wonder about the relevancy of this hierarchization process, and about how it could symbolize their potentially optional nature in the text. I decide to read them like stage directions (or, as beautifully borrowed from the Greek, didaskalía) offered by an omniscient narrator and providing the reader with a depiction of every party involved in the conversation’s feelings, seemingly lightyears away from each other although the two cohabit on a vocal track meant to become, through dexterous mastering, one.

With blink-182, the right hemisphere of my brain still believes in love and activates selective hearing for half the lines : Place your hand in mine, I want to believe that everything can still be fixed. My left-sided brain has already resigned. Are we alone? Do you feel it? Can you see that you are now nothing more than the outline of a romantic memory and that the bond that brings us together is dissipating before our eyes?

You are no longer here

I went out tonight

(I went out last night)

I cried once or twice

I met someone new

But he’s not like you

(But she’s not like you)

Hannah Diamond & Bladee - Love Goes On (Palmistry remix)

In this relationship, the damage has already been done and the superimposed dialogues mirror each lover’s worst fears. I went out tonight ; I went out last night. These paths stand perfectly parallel, meaning they won’t ever cross again. The lyric difference is barely loud enough to be perceived, but this slightly delayed beat feeds into the emotional disharmony.

You are no longer here & You did not even try

You never gave a warning sign

(I gave so many signs) […]

I couldn’t turn things around

(You never turned things around)

Taylor Swift & Bon Iver - exile

Music as an art form gets a free pass when it comes to some ethical considerations, giving its players the authority to state accusations as facts for the sake of a strong rhyme. You never turned things around, you never tried your best to keep me satisfied and save what we had built. I couldn’t turn things around, I tried my best, but my idea of best was never the same as yours.

You are no longer here & You did not even try & You act like you know everything

It’s just a cigarette and I only did it once

(It’s just a cigarette, it’ll soon be only ten)

It’s only twice a week so there’s not much of a chance

(It’ll make you sick, girl, there’s not much of a chance)

Princess Chelsea & Jonathan Bree - Cigarette Duet

Behind any dialogue line can lie another. Sometimes, what is perceptible trumps what is legible, and from a seemingly identical verse opposite meanings and sounds can arise, depending on whose lips it flows from. It’s just a cigarette, or, it’s just a cigarette. Risk awareness or paternalism? My heart never breaks as much as when words I used to find so tender in my interlocutor’s mouth start to sound irritating. Where I once saw benevolence, now sits the disdainful weight of a condescending remark. You act like you know everything and you do not try to hide it, showing off how much taller than me you consider yourself to be standing.

You are no longer here & You did not even try & You act like you know everything & You never really understood

You’re the truest light I’ve known

(I’m the one who decides who I am)

Someday I’ll learn, don’t need your fuel to burn

(I’m the one who will shed this old skin)

Sleater-Kinney - Burn, Don’t Freeze

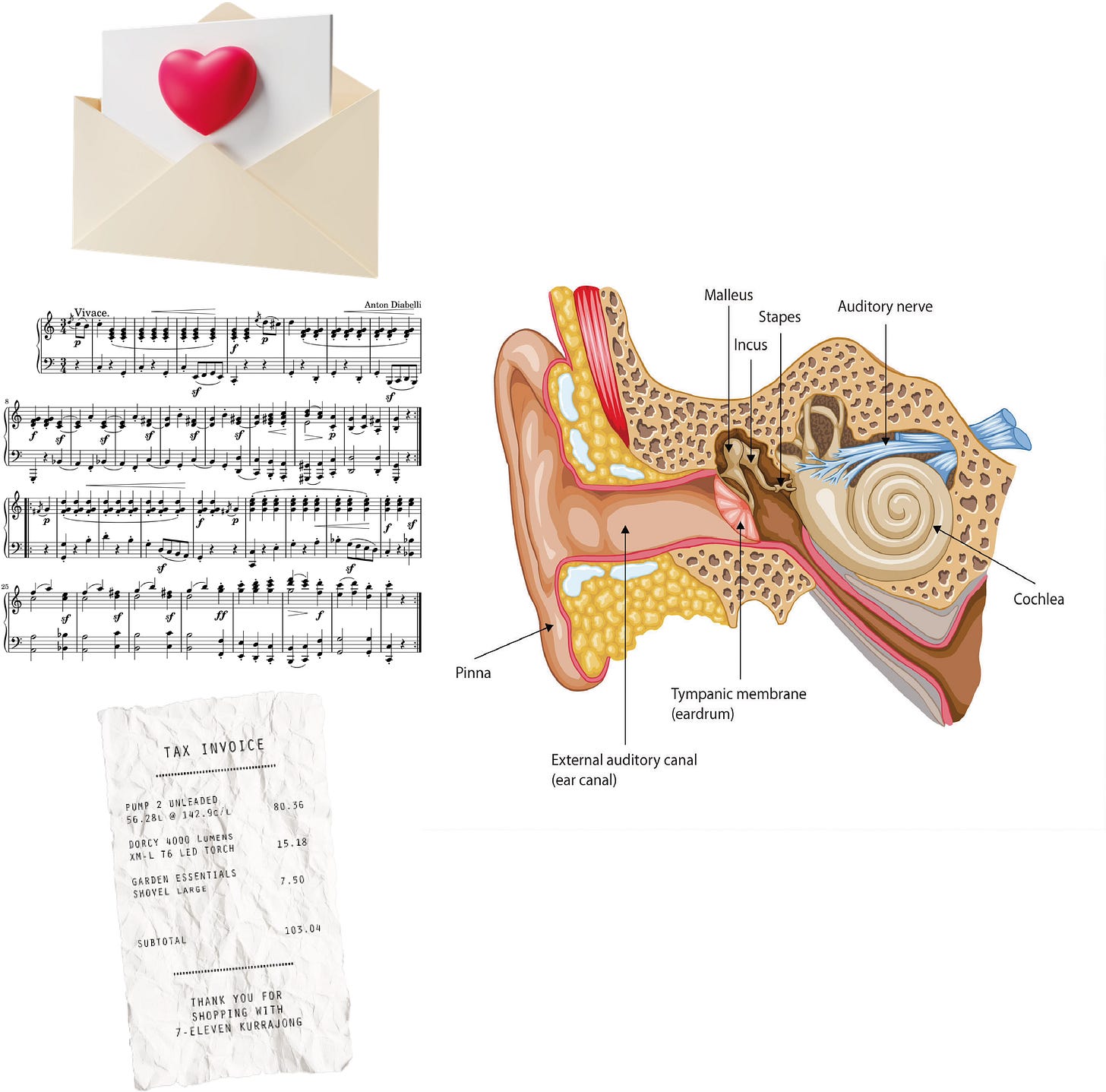

Through the essay Cognitive hearing mechanisms of language understanding: Short- and long-term perspectives, published in June 2017, neurologists Ellis, Sörqvist & Zekveld lay the grounds for a new scientific approach of cognitive hearing, relying not only on the audible aspects of speech but also on the ability to read lips and decipher sign language as well as other body talks. Certain kinds of audio signal processing (compression, distortion) and the presence of instruments can interfere with the immediate psychological comprehension of elements of language that are being presented to our ears. This brake on cognitive comprehension of lyrics expands in size when the duetted dialogue finds itself drowned in a sea of partition lines and melodic choruses.

You never heard my words correctly, you never understood me. Communication is lost even through song, and our hearts remain broken as they no longer sing in unison.

This essay was originally published in French via David Bola’s Waf Waf newsletter, available here. Translation and illustrations, all my own.